Do Cells Use a Quantum Compass to Heal Wounds?

New research reveals how muscle cells use quantum electron spin and blue light as a magnetic compass to navigate during wound healing. Discover how Earth's magnetic field guides tissue regeneration at the quantum level.

When you cut your skin or injure a muscle, countless cells immediately spring into action. They crawl toward the wound, coordinate with one another, and gradually rebuild the damaged tissue. For decades, biology has described this as a choreography of chemical gradients, mechanical cues, and genetic programs.

But a new study [1] suggests there may be another, surprising player guiding this process:

The Earth’s magnetic field – and the quantum spin of electrons.

A research team led by Fabrisia Ambrosio working with muscle progenitor cells (the stem-like cells that help repair injured muscle) has discovered evidence that these cells may use a light-activated “quantum compass” to navigate during wound healing. If correct, this would mean that electron spin helps direct how tissues regenerate.

This work not only stretches our understanding of cell biology; it also dovetails with a growing body of research in quantum biology, and connects intriguingly to the International Space Federation’s own investigations into how life taps into deeper layers of physical reality (The Memory Field: Could Quantum Biology Involve Accessing Information Stored in Space Itself?).

A Hidden Sense: Cells That Feel the Earth’s Magnetic Field

Scientists have long known that many animals can sense the Earth’s magnetic field. Migratory birds, sea turtles, and some insects appear to use a magnetic compass to navigate across vast distances. Even bacteria, tiny unicellular organisms, have magnetoreception , and although we are not consciously aware of it, some research studies have indicated that humans transduce changes in Earth-strength magnetic fields into an active neural response [2].

This video shows changes in alpha brainwave amplitude following rotations of an Earth-strength magnetic field. On the left, counterclockwise rotations induce a widespread drop in alpha wave amplitude. The darker the blue color, the more dramatic the drop.

One leading hypothesis is that this sense depends on radical pairs—pairs of electrons whose spins (Figure 1) are exquisitely sensitive to weak magnetic fields (Figure 2), including Earth’s [3].

Figure 1. Electron spin as a tiny bar magnet.

Each electron behaves like a tiny spinning cloud of charge [4], and this circulating charge produces a magnetic field. So, the electron behaves like a microscopic bar magnet. When the spin points in one direction (“spin up,” left), the electron’s north–south poles line up one way; when it points the other way (“spin down,” right), the poles reverse. The red loops show the magnetic field lines produced by this spinning charge, emphasizing that flipping the spin flips the orientation of the tiny magnet.

Figure 2. Radical pairs as tiny quantum compasses.

Light or other energy causes an electron to jump from a donor molecule (D) to an acceptor (A), creating a radical pair—two molecules each holding an unpaired electron. At first, the electron spins are opposite (the singlet state, left), but in the presence of the Earth’s magnetic field they rapidly flip back and forth between opposite and parallel alignment (the triplet state, right). Because singlet and triplet states drive different chemical reaction pathways, this spin switching steered by the geomagnetic field can change which reaction products are formed, allowing biology to “sense” magnetic direction through quantum spin chemistry. The different spin-state dependent products can then be used to orient cells, during processes like wound healing, and of course guide entire organisms via magnetoreceptive navigation.

The new study asked a bold question:

Could ordinary cells inside our bodies also be sensitive to the geomagnetic field (GMF), and could that sensitivity matter for something as basic as wound healing?

To find out, the researchers focused on muscle progenitor cells (MPCs). These are resident cells in skeletal muscle that migrate to sites of damage and fuse into new fibers during repair.

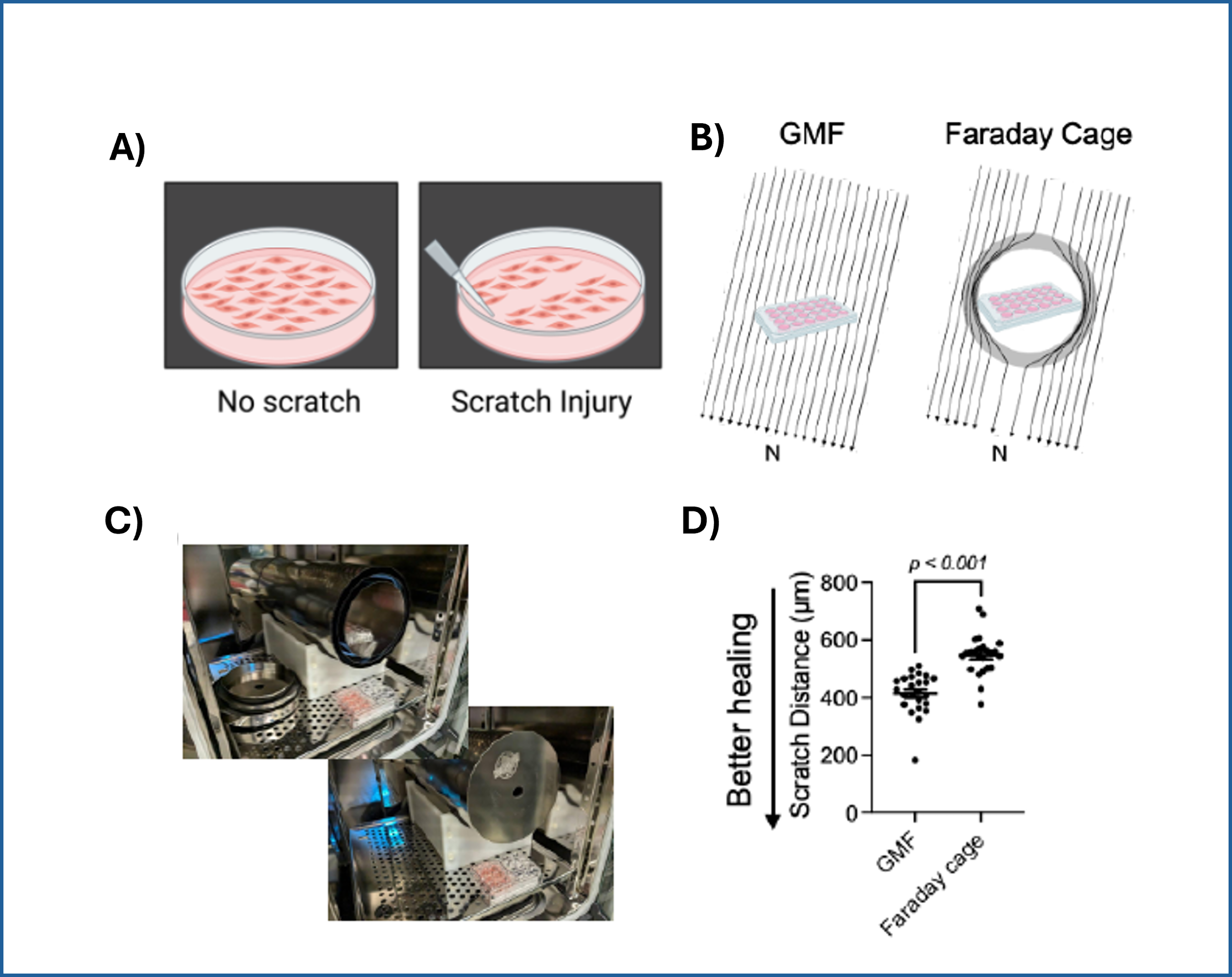

They began with a simple in-vitro injury model: They grew a flat layer of MPCs in a dish, then made a "scratch" through the layer (Figure 3), creating a gap—a miniature wound. Over several hours, the cells naturally migrated into the gap to close it.

Next, they changed a single, non-obvious parameter: the magnetic environment. In one condition, cells experienced the normal geomagnetic field (about 50 microtesla—extremely weak by everyday standards). In another, the dish was placed inside a Mu-metal Faraday cage, a shield that blocks the Earth's magnetic field, reducing it to near zero.

Figure 3: A) A standard scratch-wound healing assay used to test cell migration. The "wound" is created by physically scraping a line through a confluent cell layer, and the closure of that wound is tracked over time. This allows researchers to quantify how efficiently cells can migrate and "heal" the gap. B) Cell cultures with scratch (in 24-well plates), placed either inside a standard incubator (GMF present) or inside a Mu-metal Faraday cage (GMF blocked). C) Photograph of the scratched cells in the Mu-metal Faraday cage placed inside a cell culture incubator. D) Statistical results for scratch distance closure from control and GMF-shielded conditions with GMF group demonstrating increased wound closure (increased bio-regenerative capacity). P<0.001 indicates statistically significant difference. Images reproduced from: K. Wang et al., Electron spin dynamics guide cell motility. 2025. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2503.02923.

When the geomagnetic field was eliminated, wound closure slowed significantly. The same cells, receiving the same nutrients and temperature, simply migrated less efficiently without Earth’s gentle magnetic background.

This is striking because the energy scale associated with the geomagnetic field is millions of times smaller than ordinary thermal noise at body temperature. Classical physics would expect such a tiny field to be irrelevant. Yet the biology disagreed.

Tuning the Quantum Dial: Electron Spin and Radio Waves

To probe whether this effect was truly quantum in nature, the researchers turned to another clever test.

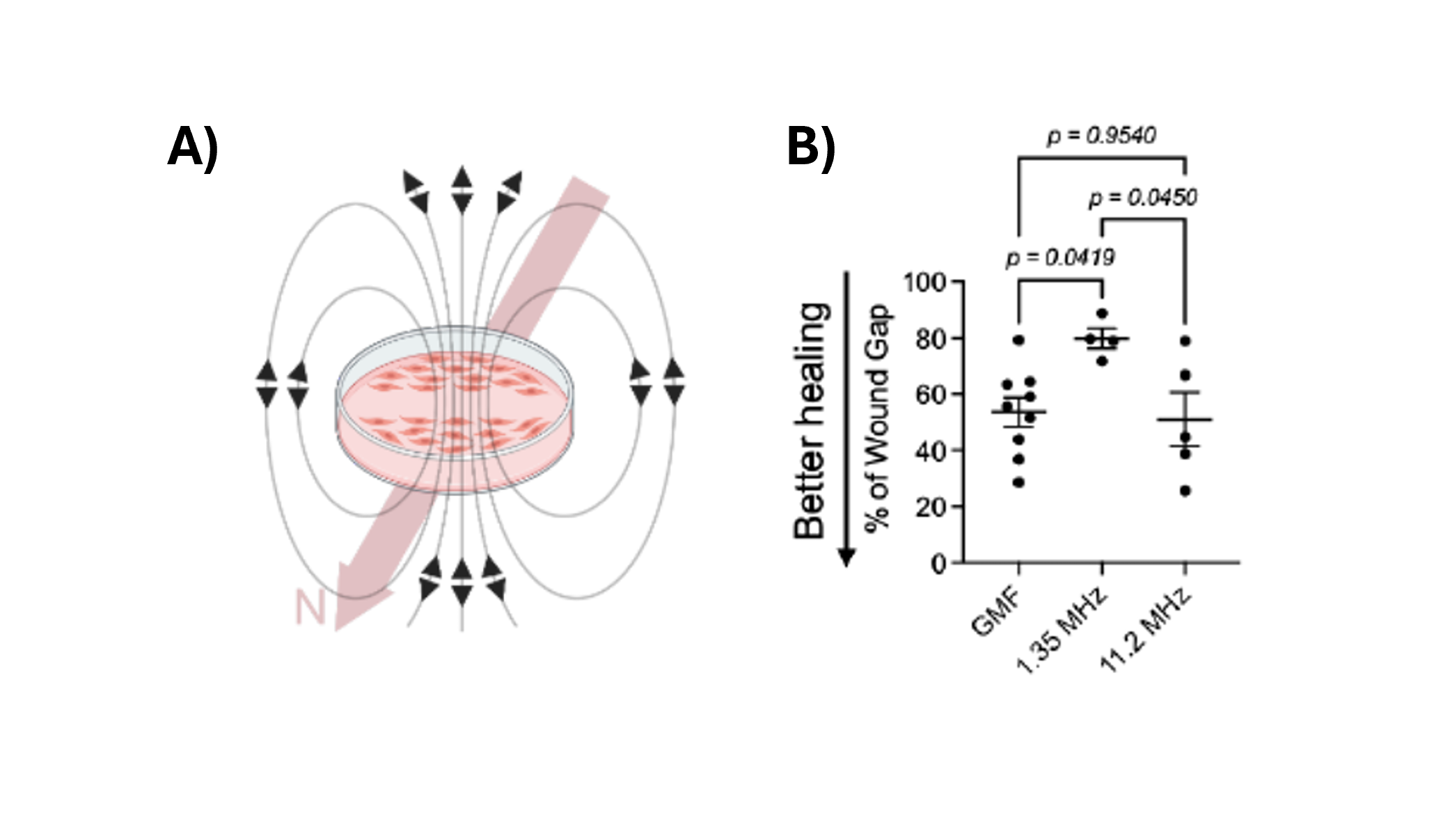

If the cells are using a radical pair mechanism—where paired electron spins act as tiny quantum sensors of the magnetic field—then disrupting the spin dynamics should interfere with the process. One way to do that is to apply a weak radiofrequency (RF) field at a specific frequency: the Larmor frequency of a free electron in the Earth’s field (about 1.35 MHz).

So, they repeated the scratch-wound assay under the normal geomagnetic field, but added either a very weak oscillating RF field at 1.35 MHz (the resonant frequency of electron spin precession in the GMF), or a control RF field at a different frequency (11.2 MHz) that should not resonate with the spins.

The result: The 1.35 MHz field reduced wound closure, while the non-resonant 11.2 MHz field had no significant effect (Figure 4).

Figure 4. A) Schematic of scratched cells in the presence of an endogenously generated oscillating EM field. The Earth’s magnetic field is illustrated by the thick pink arrow. B) Percentage of the remnant wound gap after 6 hours of 1.35 MHz or 11.2 MHz oscillating field stimulation. Scratched monolayers that were not stimulated with oscillating fields were used as controls (GMF). One-way ANOVA. n=4-9/group. Images reproduced from: K. Wang et al., Electron spin dynamics guide cell motility. 2025. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2503.02923.

This kind of sharp frequency dependence is exactly what you’d expect if electron spin states are involved. It’s far harder to explain via a purely classical mechanism.

Taken together, these experiments suggest that muscle progenitor cells are not just vaguely “sensitive” to magnetic fields—they may be using a spin-based mechanism to guide their motion. This is cellular behavior guided not by chemical cues, but by quantum cues.

Blue Light From the Wound: A Self-Illuminated Compass

The next question was: Where do the relevant electrons come from? And how are they activated?

In birds, the leading model of magnetoreception involves blue light. Photons in the blue range can excite certain proteins (like cryptochromes), creating radical pairs whose spins respond to the geomagnetic field and change downstream signaling. It is believed that this enables migratory birds to literally see the Earth's magnetic field, enabling precise navigation.

The muscle study uncovered a similar twist: When the researchers scratched the cell layer, they detected a brief but significant burst of blue light emitted by the cells themselves—an ultraweak flash invisible to the naked eye. This injury-triggered blue photon emission proved to be functionally important. When they illuminated injured cells with blue light, migration sped up and the wound closed faster—but only with the geomagnetic field present.

Figure 5. Color-dependent migration of muscle progenitor cells and a hint of spin-based healing.

(A) Schematic of the scratch-wound assay: a confluent layer of muscle progenitor cells (MPCs) in a dish is “scratched” with a pipette tip to create a gap, then allowed to heal either in the dark or under continuous illumination with white, blue (430–470 nm), green (530–570 nm), or red (630–670 nm) light. (B) Quantification of scratch distance after healing shows that blue light produces the greatest wound closure (smallest remaining gap), while dark, green light, and red light conditions leave a much wider scratch; green and red have intermediate effects from dark (no light). (C) Relative F-actin intensity, a marker of rigid cytoskeletal structure, is lowest under blue light, consistent with a more dynamic, motile state of the cells (and better wound healing, less scaring). Together, these results indicate that MPCs are selectively sensitive to blue light in a way that enhances migration, in line with a spin-dependent radical-pair mechanism where blue-light–generated electron spins, tuned by the geomagnetic field, help steer the cellular machinery that closes the wound. Images reproduced from: K. Wang et al., Electron spin dynamics guide cell motility. 2025. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2503.02923.

If they either quenched the endogenous blue photons or shielded the cells from the Earth's magnetic field, the benefit of blue light disappeared. Importantly, red and green light did not have the same effect, echoing the specific blue-light sensitivity seen in animal magnetic compasses.

Altogether, this paints a remarkable picture:

When tissue is injured, it briefly glows in blue light. That light triggers radical pairs—likely in aromatic or cofactor-containing proteins—whose electron spins are tuned by the geomagnetic field. The resulting spin dynamics feed into cell signaling pathways that control motility and wound repair.

In other words, the wound may briefly “turn on” a quantum compass that helps cells find their bearings. The orientation mechanism makes sense; however, there are also increasing studies indicating that spin-selective quantum effects help steer chemical reactions such as electron transfer—where Marcus theory shows how exquisitely sensitive electron-transfer rates are to small changes in the molecular environment—and enzymatic processes (in electron bifurcation and photo-CIDNP, a light-driven effect where spin states leave a detectable “fingerprint” on reaction products that can even be seen in NMR signals). Taken together, this suggests that the radical pair activation seen in MPCs may not only orient the cells, but may also be doing some surprisingly sophisticated quantum information–processing work inside them.

A rough analogy is to imagine a busy train station where every traveler carries either a red or green ticket. The layout of the station (like Marcus theory’s energy landscape) determines which routes are easy or hard to take, but the ticket color (the spin state) decides which doors will actually open for each traveler. A small change in lighting or signage—like a weak magnetic field or a pulse of blue light—can subtly shift who goes where, and at the end of the day, security cameras (like NMR in photo-CIDNP experiments) can look back at the crowd patterns and see a clear imprint of which ticket colors dominated which routes. In the same way, spin states inside cells can quietly gate which chemical pathways are favored, leaving a detectable “pattern” in the reaction products and, ultimately, in how the cells move and heal.

From Cell Compass to Functional Regeneration

To move beyond 2D dishes, the researchers also tested a 3D bioengineered muscle construct—a lab-grown miniature muscle. They injured the construct and then exposed it to a weak magnetic field (~400 microtesla) aligned along the direction of the muscle fibers.

They found more activated and differentiating muscle progenitor cells in the magnetically stimulated constructs, as well as stronger contractile force during regeneration compared to constructs not exposed to the field.

So the story doesn't stop at "weird quantum effects in a dish." The magnetic environment—and, by implication, electron spin dynamics—appeared to change how effectively the engineered muscle regained function.

If borne out in further studies, this would mean that tissue regeneration in vivo may quietly depend on an interplay between electron spin, ultraweak biophoton emission, and the ever-present geomagnetic field.

Why This Matters: Toward Quantum-Informed Regenerative Medicine

At first glance, this might sound like esoteric physics. But the implications are surprisingly practical.

If cells truly rely on spin-based magnetosensitivity during processes like wound healing, then magnetic environments could matter more than we realized—both in natural settings and in clinical or spaceflight contexts. Carefully tuned light and magnetic field therapies might one day enhance tissue repair, regeneration, or even stem-cell guidance. And our models of cell behavior would need to expand beyond purely biochemical and mechanical cues to include quantum-scale information processing.

The authors themselves are cautious: this is early work, done in controlled lab settings, and many details remain unknown. Which proteins host the radical pairs? How are these quantum events coupled into broader cellular networks? Can similar mechanisms be found in other tissues and cell types?

Nonetheless, the central message is powerful:

Cells are not just tiny bags of chemistry. They may also be exquisitely sensitive quantum sensors, using electron spin to align their behavior with the magnetic structure of their environment.

Connecting the Dots with ISF Research

At the International Space Federation, we’ve been following a complementary thread of research that asks a related question at a different scale: Given that spin stands alongside mass and charge as a fundamental characteristic of matter, might living systems exploit this property to organize information processing across scales—from wound healing to cognition itself? In our recent theoretical work, we are exploring whether the brain contains a mesoscopic magnetic network whose collective susceptibility sharpens with receptor co-activation. In simpler terms, when many neurotransmitter receptors in a patch of cortex are active together, they don’t just pass along electrical signals; they also form a kind of shared, spin-sensitive magnetic “neighborhood” that becomes more responsive as more receptors join in.

The core idea is that heterocyclic neurotransmitters like dopamine or serotonin—molecules with aromatic ring structures—act as tiny quantum switches when they bind to their receptors. Binding locks these ring systems into a more ordered configuration and extends the time over which their electron spins stay coherent. This creates ultra-weak magnetic near-fields (on the order of nanotesla) around the receptor sites, which can bias nearby spin chemistry and electron-transfer routes in the surrounding membrane and cytoskeleton. When many such receptors are active together, their tiny magnetic pockets can synchronize, forming the mesoscopic magnetic network described above.

In our model, this synchronized spin network does more than just sit there. Because it is being constantly “pumped” by ordinary neural metabolism and electrical activity, it can act like a parametric amplifier for certain field modes—selectively boosting specific patterns of vibration and electromagnetic fluctuation that are seeded by the quantum vacuum itself (the zero-point field). Above a certain threshold, this leads to supra-linear increases in coherence across multiple scales: from molecular pockets, to whole receptors and cytoskeletal domains, up to dendritic branches and microcircuits that track changing cognitive states. In everyday language, the brain may be using spin-based magnetic microenvironments as a way to stabilize and shape collective patterns of activity that correlate with conscious awareness.

In parallel with our work investigating information processing in subcellular networks and macromolecular quantum dynamics, these same collective dynamics arising from a spin-based magnetic field network of course extend into subcellular structures like mitochondria, microtubules, and the nucleus. It's a "nested dynamics" view of biological intelligence: multiple scales folding together through heterogeneous networks that exploit quantum information processing at multiple levels.

So the muscle progenitor cell study you've just read provides an elegant experimental snapshot that fits into this broader quantum-biology story: life seems to read and write quantum information through the electromagnetic environment at multiple scales — from single-cell navigation during wound healing, to neural oscillation and sensory binding that supports cognitive experience, all the way to the deeper fabric of how complex living structures self-organize.

Seen in this light, the new muscle-cell study is not an odd curiosity but part of a larger pattern. In both systems, biology appears to rely on spin-sensitive aromatic structures and radical pairs to read out and amplify extremely subtle fields—Earth’s geomagnetic field in the case of wound-healing cells, and internally generated magnetic near-fields in the case of neural tissue. In muscle progenitor cells, this spin chemistry helps migrating cells find and repair an injury. In our ISF framework for the brain, similar physics may help neurons align into coherent networks that underlie perception and consciousness. Both lines of work point to the same deeper message: life doesn’t just react to chemicals and voltages; it may also be tuned to the hidden spin-structured fabric of its environment, from the geomagnetic field all the way down to the quantum vacuum.

A New Frontier: Quantum Compasses in Every Cell?

We're still in the early days of this exploration. Many questions remain: How widespread are these spin-based compasses across cell types? Can they be tuned or enhanced in therapeutic contexts? Do similar mechanisms play roles in development, cancer metastasis, or neural growth?

What's becoming clear is that quantum effects are not confined to exotic laboratories or theoretical thought experiments. They're present in the everyday business of living cells: in how they move, sense, remember, and heal.

As we continue our work at ISF—probing the interfaces between quantum physics, biology, and spacetime—we see studies like this as signposts. They point toward a future where regenerative medicine, neuroscience, and even our understanding of consciousness may be reframed in the light of quantum-informed biology.

And perhaps, the next time you skin your knee or strain a muscle, you’ll have a new appreciation for what might be happening behind the scenes: a faint flash of blue light, a whisper of electron spin, and a tiny quantum compass helping your cells find their way home.

References

1) K. Wang et al., Electron spin dynamics guide cell motility. 2025. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2503.02923.

2) C. X. Wang et al., “Transduction of the Geomagnetic Field as Evidenced from alpha-Band Activity in the Human Brain,” eNeuro, vol. 6, no. 2, Mar. 2019, doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0483-18.2019.

3) P. J. Hore, “Radical quantum oscillations,” Science, vol. 374, no. 6574, pp. 1447–1448, Dec. 2021, doi: 10.1126/science.abm9261.

4) C. T. Sebens, “How Electrons Spin,” Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part B: Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics, vol. 68, pp. 40–50, Nov. 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.shpsb.2019.04.007.